I really want to blog more. The problem is that most of the posts to

this blog are fairly long-form. This will probably change as I do blog

more. I've also moved to Pandoc for rendering posts via ikiwiki-pandoc. In that process, I've also come to realize that pandoc handles org-mode files almost completely

unambiguously—which is not actually something you get in most markup

languages/markup language interpreters. BONUS: I enjoy writing in

org-mode. As is my wont, I've also created some (not-so) fancy scripts to help

me: Needed to revoke your key should the master signing/certifying key

ever be compromised store printed revocation cert in file or safe-deposit box Download paperkey and its gpg signature Get David Shaw's public key (0x99242560) from your keyserver of

choice Verify you have downloaded the right paper key and that the level of

trust is sufficient for your purposes If you have a good signature from davidExtract and install Print you secret key Store it in your file or safe-deposit-box By default, GnuPG creates a key for signing and an encryption

subkey: You can add a new subkey with the command And then you should see You can then remove your certification master key (make sure you've

gone through the key backup process before you

do this!) Now See also: Usually when I need to delete a commit from a local git repo I

use: This starts an interactive rebase session for all commits from

This is fine if you’re there to drive an editor for an interactive

rebase. The problem with interactive rebase is you can’t easily script

it. At work I help to maintain our “beta cluster” which is a bunch of

virtual machines that is supposed to mirror the setup of production. The

extent to which production is actually mirrored is debatable; however,

it is true that we use the same puppet repository as production.

Further, this puppet repository resides on a virtual machine within the

cluster that acts as the beta cluster’s puppetmaster. Often, to test a patch for production puppet, folks will apply

patches on top of beta’s local copy of the production puppet repo. The problem here is that a lot of these commits are old and

busted. It’d be nice to have a script that periodically cleans up these

patches based on some criteria. This script would have to potentially be

able to remove, say, The way to do this is with Selective quoting of The commits we want are all the commits surrounding

So we really want to take the commits Tada! Commit gone. From This is the same revision that is returned by Where it seems awesome is in combination with I could see running this in a panic: Found via a comment on

hackernews Today I was working with a PDF that was 27,000 pages long (god help

me). I never tried to open that PDF. This is just the page count I got

from a python script I wrote to parse that PDF to a CSV file. When the time came to spot-check the results of that python script I

needed to compare some pages deep within the PDF with the output on the

CSV file. I use the Zathura

document viewer to view PDFs, but I was reasonably certain that it would

choke on such a large document. Instead I extracted one page at a time

using ImageMagick. Then I opened the generated PDF using Zathura. I was able to compare that side-by-side with the generated CSV. Easy peasy. A jargon-less definition of code review is a difficult thing to pin-

down. Code review is what happens when someone submits some code to a

software project and a different person, who has knowledge about that

project, checks to see if there are any problems in the submitted code

before making the submitted code a part of the project. Code review is based around the simple idea that with enough eyes all

bugs are shallow. Given a large enough beta-tester and co-developer base, almost every

problem will be characterized quickly and the fix obvious to

someone. – Linus’s Law, ESR, The

Cathedral and the Bazaar This is all part of a collaborative model of

software development. A model in which anyone can submit code or

feedback to an open project. This model is the engine that drives the

development of some of the world’s largest and most successful software

projects. It’s an accepted Good Thing™. It is tested. It works. As a

result, almost every software project uses code review for almost every

code change—big or small. Code review is meant to ensure that only high-quality code can be

merged into a project. Code review may be used for many other purposes,

some good and some bad. Code review at its best is a Socratic teaching style. Many software projects are large, tangled, and, sometimes, confusing.

A sweeping change can create regressions, or be disruptive rather than

helpful. Software functions as an interconnected system, and to learn to

work within that system you must learn how that system came into

being. A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from

a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch

never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start

over with a working simple system. – Gall’s Law, John Gall, Systemantics: How Systems Really Work and

How They Fail Through code review a newcomer learns about the design of the

project—to work with the project’s design rather than against it. And by

working with the design of a system, to work more effectively within

it. When review is done well, the person who’s code is being reviewed may

learn about software design, general debugging, the management of open

projects, the underlying language, or the underlying language’s

implementation. For better or worse, every project has a culture. The culture that is conveyed through review may be completely

innocuous. The propensity of a particular project to favor third-party

libraries versus maintaining their own implementations in the project.

How much trust a particular project puts in third-party entities (Jira,

Github, Gitlab, etc.). The tools and best-practices for a project also

often become obvious during code review. For instance, whether a project

accepts pull requests via Github or not. Meaningful cultural norms are also conveyed via code review. A

project may have a culture that is generous and helpful, or it may be

openly hostile to outside contribution. Ultimately, the person reviewing

code has power over the person submitting code. This power dynamic can

become even larger when the person submitting code is a member of a

marginalized group in the society of the person reviewing the code. The person who is reviewing (hopefully) has some sense of the power

imbalance that is inherent in the code review process. It is often

dishearteningly uncomfortable to give code review—particularly when you

disagree with some of the code’s implementation. Code reviewers should

(and often do) work hard to offer constructive feedback and to avoid

hostile interactions. Code review, from the perspective of the person who submits code, is

a situation where you’re interacting with a person who has no real

incentive to be nice. Code review is a situation that can tell you a lot

about a person. I’m far from a master when it comes to code review. I’ve done my share of review, and I’ve had my share of reviews—both

good and bad. These are the things I try to remain mindful of during the

review process—both as patch-submitter and as a reviewer. It takes time It takes a LOT of time. I spend so much time on each review because I

want to offer helpful and meaningful feedback. I could easily spend my

entire working day reviewing code (and sometimes, I do). I’ve seen rules and guidelines for how much time you should take for

each SLOC in a review, but I think that’s meaningless. If I haven’t

reasonably considered the consequences of a change—I’m not done

reviewing the code. When you submit a patch, you should be mindful that review takes

time. If this is a one-line change that you want rubber-stamped, then

you should be explicit about that. Honestly, I’m pretty OK

rubber-stamping the work of peers that I trust; however, asking for code

review on that one line means that I will spend at least 15 minutes

mentally shifting gears, examining, running, and otherwise poking-at the

code. There is no better way to exhaust the patience and goodwill of a

software project than to continually submit obviously untested changes.

Have you run the code? If not, the code is not ready for

review. If everything is OK, then everything is OK Sometimes, I can’t find anything wrong with a large patch that was

just submitted. If that’s the case, I try to not to penalize that

patch—I don’t go back through the patch and really

scrutinize the method names, I don’t suggest libraries that do the same

thing but in a way I slightly prefer, I don’t enumerate the approaches

that could have been taken. I just post, “+1 lgtm” and that’s all I have

to show for the hour of work I just put in reviewing, but I think that’s

OK. I feel like this is part of project culture. If a person you don’t

know submits a good patch, that should be OK. Say something nice This is probably my own weird insecurity. For each review, I go

through and make sure to leave comments about some of the things I like

in the patch. I know that whomever I am reviewing is my intellectual

equal (or often intellectual better), and that they’ve just put a lot of

time into this patch. I also know that when I’ve put a lot of time into

something, and all of its redeeming qualities are ignored it stinks, and

sometimes it fucks up my day. I try not to fuck up anyone’s day. Nitpicks and show-stoppers When I review things, I try to be explicit if I can—“Fix this

problem, and I’ll merge the patch.” There are times I may feel strongly

that a piece of code can be improved, but not strongly enough to reject

the patch—“Nitpick: could use a comment here”. I’ll reply overall with,

“Some nitpicks inline, but overall lgtm” and then ask in IRC if they’re

fine with the patch merging as-is. The difference between a nitpick and a show-stopper is important when

there are both types of problems in one patch. How do I know what

really needs fixing versus (what really amounts to) the

way the reviewer would have written the same patch? Code review is slow (by design) and hard to get right. Also (CAUTION:

controversy ahead), some changes don’t need review.

That is, they’re not important to the overall code function, and can be

corrected easily. Adding a section to a README, or adding to the docs:

JFDI. If there’s a spelling error, well, someone will fix it. When you have to deploy a hot-fix to production because production is

completely broken: JFDI. I don’t like being a roadblock for things like this. There are many

code-review systems that force you to gate changes like this.

Ultimately, I think this creates something akin to alarm-fatigue but for

code review. It hurts everyone involved, it hurts the process, and could

cause some resentment. I suppose the tl;dr here is: Code review is good

when its done well, and bad when it’s done poorly. Earth shaking stuff,

believe me—I know. My big, bold, and important message about code review is—as with all

processes that involve people—staying mindful that everyone involved is,

in fact, a person is paramount to the process’s success. I know that Linode has had its share of problems

recently, but it's a service I won't be leaving any time soon. In July of 2014, as part of the Electronic Frontier Foundation's Tor Challenge I decided to

build a Tor node. Not only did I decide to build a Tor node, I decided

to build an exit node. Running an exit node means that

instead of passing traffic to another node on the Tor network, my node

will be where Tor traffic exits the network, so it'll be my IP address

that any end-points see as the source of traffic. When I decided to run an exit node, I was using Comcast as my

ISP—running a Tor exit node is definitely against Comcast's Terms of

Service (TOS). By this point, I had been using Linode for many years to

host a bunch of personal web projects, and I had no complaints. On a

whim I perused the Linode

TOS: Linode does not prohibit the use of distributed, peer to peer network

services such as Tor, nor does Linode routinely monitor the network

communications of customer Linodes as a normal business practice. So with that, I created intothetylerzone

(because naming things is hard). It's a fast (1MB/s), stable, exit node

supporting exits on a number of ports: My Tor exit node is sometimes abused. There are fewer abuse-reports

than I would have expected—I probably get 1 report every 3 or 4 months.

I just handled an abuse report today from Linode (heavily edited): We have received a report of malicious activity originating from your

Linode. It appears that your Linode is being used to scan hosts. We ask

that you investigate this matter as soon as you are able. There was a follow-up message on the ticket with the specific IPs

that were being scanned. I blocked any exit to those targeted IPs in my

This router is part of the Tor Anonymity Network, which is dedicated

to providing people with anonymity who need it most: average computer

users. This router IP should be generating no other traffic. While Tor is not designed for malicious computer users, it is

inevitable that some may use the network for malicious ends. In the mind

of this operator, the social need for easily accessible

censorship-resistant anonymous communication trumps the risk. Tor sees

use by many important segments of the population, including whistle

blowers, journalists, Chinese dissidents skirting the Great Firewall and

oppressive censorship, abuse victims, stalker targets, the US military,

and law enforcement, just to name a few. I've updated my /etc/tor/torrc to include all ports on the

destination IP: ExitPolicy reject [targeted-ip]:* I've also restarted the tor service. The destination IP should no

longer receive any traffic from this machine. Not 5 minutes later this reply came: Hi, Thank you for your response. At this time, it looks like we can

consider this case resolved. We will continue to monitor for additional

complaints and let you know should we receive more. I’ve set this ticket to close automatically in 48 hours, so there’s

no need to respond since this case is now resolved. Let us know if there's anything else we can do for you, and we'll be

happy to help. <3 Linode. Without Linode I would be unable to host a stable and fast node.

Linode supports online freedom, so I support Linode. While I was looking through my I've had the First, it seems that The easiest way I could find to view what properties are available to

colorize is to search for The other neat thing I learned is that you can include other config

files by adding an By combining these two tricks, you can create one colorscheme for a

terminal that uses the Tomorrow Theme

and one for the terminal that uses Solarized and swap

between them easily by swapping the symlink pointed at by I wish the symlink swap didn't have to happen – I wish you could just

use environment variables. As far as I can tell the only variables that are expanded in I feel like there are some other neat tricks to uncover here, but I

haven't quite grokked this to fullness just yet. Today I went to coffee with a buddy of mine from

We spent a good chunk of time looking at Wireshark captures of an

HTTP request. It got muddled and we got off-track because we were

looking at an HTTPS request and we started talking about TLS1.2,

CLIENT-HELLO, and the TLS handshake in general. I eventually found the source

for what I was yammering about. Due to how TCP estimates the capacity of a connection (i.e. TCP Slow

Start), a new TCP connection cannot immediately use the full available

bandwidth between the client and the server. Because of this, the server

can send up to 10 TCP packets on a new connection (~14KB) in first

roundtrip, and then it must wait for client to acknowledge this data

before it can grow its congestion window and proceed to deliver more

data. After I got home and ate some ice cream, I did some more reading

trying to understand this stuff. I think a lot of what was confusing

about the Wireshark stuff we were looking at is it also had TLS1.2 mixed

in there. Requesting a plain-old HTTP, port 80 site made looking at

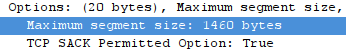

packets a bit more sane. It seems like the size of a TCP packet is negotiated during the

The MSS is derived from the MTU and is (at most?) the MTU minus the

40 bytes used for the TCP header and the IP header, so my machine sent

the MSS size of 1460 to the server in the So the data portion of a TCP segment sent in this particular

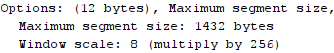

connection should never exceed 1460 bytes. While we were looking at Wireshark packet captures we kept noticing a

TCP segment size of 1486 in the “length” column with a TCP segment data

length of 1432. I noticed that my webserver sent an MSS size of 1432,

which I suppose became the limiting factor in how much data could be

sent per segment (rather than the 1460 MSS sent by my client – the

browser): Each TCP segment had a header-size of 20 bytes, so that leaves 34

unexplained bytes which (I guess) were part of the IP header. So why try to squeeze a website into ~14KB? Seems like you should be

trying to squeeze it into 1432 bytes. I found my answer in IETF RFC 6928 – a

proposal to increase the TCP Initial Window to 10 segments. The Initial

Congestion Window ( I checked the value of And it is indeed set to 10. This means that my server can send OR around 14KB of data can be sent to a browser before

another round-trip from the client to the webserver has to happen. So, overall, a nice, relaxing coffee and catch-up session with an old

coworker. Git annex goes mindbogglingly deep. I use git annex to manage my photos – I have tons of RAW photos in

Whenever I'm done editing a set of raw files I go through this song

and dance: And magically my raw files are available on s3 and my home NAS. If I jump over to a different machine I can run: Now that raw file is available on my new machine, I can open it in

Darktable, I can do whatever I want to it: it's just a file. This is a pretty powerful extension of git. While I was reading the git annex

internals page today I stumbled across an even more powerful

feature: metadata. You can store and retrieve arbitrary metadata about

any git annex file. For instance, if I wanted to store EXIF info for a

particular file, I could do: And I can drop that file and still retrieve the EXIF data This is pretty neat, but it can also be achieved with git

notes so it's nothing too spectacular. But git annex metadata doesn't quite stop there. My picture directory is laid out like this: I have directories for each year, under those directories I create

directories that are prefixed with the ISO 8601 import date for the photo,

some memorable project name (like I got this system from Riley Brandt (I can't

recommend the Open Source Photography Course enough – it's amazing!) and

it's served me well. I can find stuff! But git annex really expands the

possibilities of this system. I go to Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP) multiple times per year.

I've taken a lot of photos there. If I take a trip there in October I

will generally import those photos in October and create But what happens if I want to see all the photos I've ever taken in

RMNP? I could probably cook up some script to do this. Off the top of my

head I could do something like Now the thing that was really surprising to me, you can filter the

whole pictures directory based on a particular tag with git annex by

using a metadata

driven view. I can even filter this view using other tags with

This feature absolutely blew my mind – I dropped what I was doing to

write this – I'm trying to think of a good way to work it into my photo

workflow #!/usr/bin/env bash

set -eu

POST=$*

BLOG_DIR=$(grep '^srcdir' ~/ikiwiki.setup | cut -d':' -f2 | xargs)

DATE=$(date -Ins)

BLOG_PATH=$(date +'blog/%Y/%m/%d')

EXT='.org'

SAFE_POST=$(echo "$POST" | \

tr '[:upper:]' '[:lower:]' | \

sed -e 's/\W/-/g')

OUT="${BLOG_DIR}/${BLOG_PATH}/${SAFE_POST}${EXT}"

mkdir -p "$(dirname "$OUT")"

{

printf '#+TITLE: %b\n' "$POST"

printf '\n' "$POST"

printf '[[!meta <span class="error">Error: cannot parse date/time: %b</span>]]\n\n' "$DATE"

} >> "$OUT"

# http://www.emacswiki.org/emacs/EmacsClient

exec emacsclient --no-wait --alternate-editor="" --create-frame "$OUT"Revocation Cert

gpg --output \<tyler@tylercipriani.com\>.gpg-revocation-certificate --gen-revoke tyler@tylercipriani.com

lpr \<tyler@tylercipriani.com\>.gpg-revocation-certificate

shred --remove \<tyler@tylercipriani.com\>.gpg-revocation-certificateKey backup

wget -c http://www.jabberwocky.com/software/paperkey/paperkey-1.3.tar.gz

wget -c http://www.jabberwocky.com/software/paperkey/paperkey-1.3.tar.gz.siggpg --search-keys 'dshaw@jabberwocky.com'gpg --verify Downloads/paperkey-1.3.tar.gz.sig paperkey-1.3.tar.gz

gpg: Signature made Thu 03 Jan 2013 09:18:32 PM MST using RSA key ID FEA78A7AA1BC4FA4

gpg: Good signature from "David M. Shaw <dshaw@jabberwocky.com>" [unknown]

gpg: WARNING: This key is not certified with a trusted signature!

gpg: There is no indication that the signature belongs to the owner.

Primary key fingerprint: 7D92 FD31 3AB6 F373 4CC5 9CA1 DB69 8D71 9924 2560

Subkey fingerprint: A154 3829 812C 9EA9 87F1 4526 FEA7 8A7A A1BC 4FA4tar xvzf paperkey-1.3.tar.gz

rm paperkey-1.3.tar.gz

cd paperkey-1.3

./configure

make

sudo make installgpg --export-secret-key tyler@tylercipriani.com | paperkey | lprSubkeys

gpg --list-keys tyler

pub

rsa4096

2014-02-19

[SC]

6237D8D3ECC1AE918729296FF6DAD285018FAC02

uid

[ultimate]

Tyler

Cipriani

<tyler@tylercipriani.com>

sub

rsa4096

2014-02-19

[E]

gpg --edit-key tyler

gpg> addkeygpg --list-keys tyler

pub

rsa4096

2014-02-19

[SC]

6237D8D3ECC1AE918729296FF6DAD285018FAC02

uid

[ultimate]

Tyler

Cipriani

<tyler@tylercipriani.com>

sub

rsa4096

2014-02-19

[E]

sub

rsa4096

2016-09-02

[S]

[expires:

2018-09-02]

gpg --export-secret-subkeys tyler > subkeys

gpg --delete-secret-key tyler

gpg --import subkeys

shred --remove subkeysgpg --list-keys shows a # next to sec#

next to my [SC] key. This indicates that

the key is no longer accessible.sensible-editor is a shell script in

Debian at /usr/bin/sensible-editor that

selects a sensible editor.sensible-{browser,editor,pager}git rebase -iHEAD..@{u}. Once I’m in the git rebase editor I put a

drop on the line that has the commit I want to delete and

save the file. Magic. Commit gone.drop c572357 [LOCAL] Change to be removed

# Rebase dbfcb3a..c572357 onto dbfcb3a (1 command(s))

#

# Commands:

# p, pick = use commit

# r, reword = use commit, but edit the commit message

# e, edit = use commit, but stop for amending

# s, squash = use commit, but meld into previous commit

# f, fixup = like "squash", but discard this commit's log message

# x, exec = run command (the rest of the line) using shell

# d, drop = remove commit

#

# These lines can be re-ordered; they are executed from top to bottom.

#

# If you remove a line here THAT COMMIT WILL BE LOST.

#

# However, if you remove everything, the rebase will be aborted.

#

# Note that empty commits are commented outThe problem with interactivity

root@puppetmaster# cd /var/lib/git/operations/puppet

root@puppetmaster# git apply --check --3way /home/thcipriani/0001-some.patch

root@puppetmaster# git am --3way /home/thcipriani/0001-some.path

root@puppetmaster# git status

On branch production

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/production' by 6 commits.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

nothing to commit, working directory cleanroot@puppetmaster# git log -6 --format='%h %ai'

ad4f419 2016-08-25 20:46:23 +0530

d3e9ab8 2016-09-05 15:49:48 +0100

59b7377 2016-08-30 16:21:39 -0700

5d2609e 2016-08-17 14:17:02 +0100

194ee1c 2016-07-19 13:19:54 -0600

057c9f7 2016-01-07 17:11:12 -080059b7377 while leaving all the others

in-tact, and it would have to do so without any access to

git rebase -i or any user input.Non-interactive commit deletion

git rebase --onto.man git-rebaseSYNOPSIS

git rebase [--onto <newbase>] [<upstream>]

DESCRIPTION

All changes made by commits in the current branch but that are not

in <upstream> are saved to a temporary area. This is the same set

of commits that would be shown by git log <upstream>..HEAD

The current branch is reset to <newbase> --onto option was supplied.

The commits that were previously saved into the temporary area are

then reapplied to the current branch, one by one, in order.59b7377 without 59b7377.root@puppetmaster# git log --format='%h %ai' 59b7377..HEAD

ad4f419 2016-08-25 20:46:23 +0530

d3e9ab8 2016-09-05 15:49:48 +0100

root@puppetmaster# git log --format='%h %ai' @{u}..59b7377^

5d2609e 2016-08-17 14:17:02 +0100

194ee1c 2016-07-19 13:19:54 -0600

057c9f7 2016-01-07 17:11:12 -080059b7377..HEAD and

rebase them onto the commit before 59b7377 (which is

59b7377^)root@puppetmaster# git rebase --onto 59b7377^ 59b7377

root@puppetmaster# git log -6 --format='%h %ai'

ad4f419 2016-08-25 20:46:23 +0530

d3e9ab8 2016-09-05 15:49:48 +0100

5d2609e 2016-08-17 14:17:02 +0100

194ee1c 2016-07-19 13:19:54 -0600

057c9f7 2016-01-07 17:11:12 -0800

d5e1340 2016-09-07 23:45:25 +0200gitrevisions(7)SPECIFYING REVISIONS

:/<text>, e.g. :/fix nasty bug

A colon, followed by a slash, followed by a text, names a commit whose

commit message matches the specified regular expression. This name

returns the youngest matching commit which is reachable from any ref.

The regular expression can match any part of the commit message. To

match messages starting with a string, one can use e.g. :/^foo. The

special sequence :/! is reserved for modifiers to what is matched.

:/!-foo performs a negative match, while :/!!foo matches a literal !

character, followed by foo. Any other sequence beginning with :/! is

reserved for now.git log --grep '<regex>' -1git revert

or git commit --fixupgit revert --no-edit ':/that thing that broke'

git commit

git push origin HEAD:refs/for/masterconvert 'big.pdf[2000]' big-pg2000.pdfzathura big-pg2000.pdf

Review as a pedagogical tool

Review as culture

Mindful review

A blatant disregard for best practice, A.K.A. JFDI.

Conclusions

ExitPolicy accept *:22 # ssh

ExitPolicy accept *:465 # smtps (SMTP over SSL)

ExitPolicy accept *:993 # imaps (IMAP over SSL)

ExitPolicy accept *:994 # ircs (IRC over SSL)

ExitPolicy accept *:995 # pop3s (POP3 over SSL)

ExitPolicy accept *:5222 # xmpp

ExitPolicy accept *:6660-6697 # allow irc ports, very widely

ExitPolicy accept *:443 # http is dead

ExitPolicy accept *:80 # but not *that* dead

ExitPolicy reject *:* # no other exits allowed

/etc/tor/torrc and replied to the ticket

(most of this language comes from the operator-tools

exit notice html):

~/.gitconfig today, I learned some new

tricks.color section in my ~/.gitconfig without really understanding

it:[color]

ui = truegit config color.ui true is superfluous as it

has been set to true by default since Git

1.8.4. More importantly, I learned that you can customize the colors of

git-branch, git-diff, git-status, git log --decorate, git-grep, and git {add,clean} --interactive<slot> on

the git-config man page.include section in your

~/.gitconfig:[include]

path = ~/.config/git/colors.config~/.config/git/color.config# Tomorrow Night Eighties in ~/.config/git/tomorrow-night-eighties.config

# Included in ~/.gitconfig via:

# [include]

# path = ~tyler/.config/git/tomorrow-night-eighties.config

[color "status"]

header = "#999999"

added = "#99cc99"

changed = "#f2777a"

untracked = "#ffcc66"

branch = "#2d2d2d" "#6699cc"

# Because the phrase "Detached HEAD" isn't unnerving enough

nobranch = bold ul blink "#f99157"

[color "diff"]

meta = "#515151"

func = "#cc99cc"

frag = "#66cccc"

context = "#999999"

old = "#f2777a" "#393939"

new = "#bef2be" "#515151"~/.gitconfig are ~

to point at the current user's home directory and ~[user] points to [user]'s home directory.include also fails silently by

design.$DAY_JOB - 2. During coffee we were discussing all the folk

theories of “fast” websites. I made some off-the-cuff remark that I

didn’t really understand – that you should try to squeeze the most

important bits of your website into the first X bytes

(X being a value I didn’t remember) for an opaque reason that

has to do with TCP congestion algorithms that I’ve never understood.

SYN, SYN-ACK phase of the TCP three-way

handshake. In the Options section of the TCP segment

(for a segment that has the SYN-flag set in the TCP segment

header) a sender or receiver may indicate a Max Segment Size (MSS). An

MSS is derived from a machine’s Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU). In the

case of my machine the MTU is set to 1500. I found this via the

ip command:tyler@magneto:~$ ip -4 link show dev wlp3s0

2: wlp3s0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc mq state UP mode DORMANT group default qlen 1000Options section

of the SYN TCP segment that it initially sent my webserver.

cwnd) is the maximum number of bytes

that a server can send without receiving any acknowledgement that the

bytes were received via a client ACK packet. This maximum number of

bytes to send is calculated by multiplying some number by MSS.

As of RFC 6928 some number is equal to 10 (initially).cwnd on some established

connections on my server:tyler@magneto:~$ sudo ss -ti

...cwnd:10...cwnd * MSS bytes of

information before the client has to acknowledge that anything has been

receieved. So, in the case of the Wireshark connection I recorded, my

webserver can send 1432 * 10 bytes, or 14320 bytes:tyler@magneto:~$ units

Currency exchange rates from www.timegenie.com on 2016-06-22

202926 units, 109 prefixes, 88 nonlinear units

You have: 14320 bytes

You want: kilobytes

* 14.32

/ 0.069832402~/Pictures that are backed-up to a few git

annex special remotes.cd raw

git annex add

git annex copy --to=s3

git annex copy --to=nas

git commit -m 'Added a bunch of files to s3'

git push origin master

git push origin git-annex

git annex dropcd ~/Pictures

git fetch

git rebase

git annex get [new-raw-file]git annex metadata 20140118-BlazeyAndTyler.jpg --set exif="$(exiftool -S \

-filename \

-filetypeextensions \

-make \

-model \

-lensid \

-focallength \

-fnumber \

-iso 20140118-BlazeyAndTyler.jpg)"$ git annex drop 20140118-BlazeyAndTyler.jpg

drop 20140118-BlazeyAndTyler.jpg (checking tylercipriani-raw...) (checking tylercipriani-raw...) (checking tylercipriani-raw...) ok

(recording state in git...)

$ git annex metadata --get exif !$

git annex metadata --get exif 20140118-BlazeyAndTyler.jpg

FileName: 20140118-BlazeyAndTyler.jpg

Make: SAMSUNG

Model: SPH-L720

FocalLength: 4.2 mm

FNumber: 2.2

ISO: 125Random background

Pictures/

└── 2015

└── 2015-08-14_Project-name

├── bin

│ └── convert-and-resize.sh

├── edit

│ ├── 2015-08-14_Project-name_00001.jpg

│ └── 2015-08-14_Project-name_00002.jpg

└── raw

└── 2015-08-14_Project-name_00001.NEFmom-birthday or rmnp-hike). Inside that directory I have 2

directories: raw and edit. Inside each one of those directories, I

have photos that are named with ISO 8601 import date, project name, and

5-digit import number and a file extension – raw files go in raw and edited/finished files edit.Fictional, real-world, totally real actually happening scenario

2015/2015-10-05_RMNP-hike/{raw,edit}, and then

if I go there again next March I'd create 2016/2016-03-21_RMNP-daytrip-with-blazey/{raw,edit}.

So if I want to preview my RMNP edited photos from October I'd go:cd 2015/2015-10-05_RMNP-hike/edit

git annex get

geeqie .find . -iname '*rmnp*' -type l, but that would

undoubtedly miss some files from a project in RMNP that I didn't name

with the string rmnp. Git annex gives me a

different option: metadata tags.Metadata views

$ tree -d -L 1

.

├── 2011

├── 2012

├── 2013

├── 2014

├── 2015

├── 2016

├── instagram

├── lib

├── lossy

├── nasa

└── Webcam

$ git annex view tag=rmnp

view (searching...)

Switched to branch 'views/(tag=rmnp)'

ok

$ ls

alberta-falls_%2015%2016-01-25_cody-family-adventuretime%edit%.jpg

Elk_%2016%2016-05-01_wikimedia-reading-offsite%edit%.jpg

Reading folks bing higher up than it looks_%2016%2016-05-01_wikimedia-reading-offsite%edit%.jpggit annex vfilter tag=whatever. And I can continue to edit,

refine, and work with the photo files from there.

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted

Posted